Following is the story Mike Olson read to the banquet audience:

Before I start my story, I just want to issue an apology to Ms. Linda Anderson. Being a naughty and somewhat rebellious student, I went out of my way to get a rise out of her.

[“It worked!” Linda shouted from the audience].

As an example of my antics, I once turned in a paper titled, “Sex Crazed Love Godesses.” When I got my graded paper back, Linda’s diplomatic response was, “Title is a little inappropriate.” I think you’ll be happy to hear that I went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in English and now make my living as a writer.

The Flag

I thought it would be fun to clear up a little North Platte mystery tonight. Quite a few of you know parts of this story, but few people know all of it.

I imagine that most adolescents go through a phase of pre-adulthood where they yearn to cast off the yoke of decent, socially-acceptable behavior and flip the bird to the establishment.

Let me take you back to the summer before we entered Senior High. If you’ll remember, in 1980, international news was all about U.S.-Soviet relations. The Soviets had invaded Afghanistan, the U.S. imposed a grain embargo and boycotted the Moscow summer Olympics. The 53 Americans were still held hostage in Iran and Jimmy Carter’s presidency was winding down.

Being a mildly rebellious 15-year old, growing up in a conservative Nebraska city, this socially tense environment was a very attractive target for a practical joke. My older brother another friend, Joe and I longed for an opportunity to stir the ants’ nest and ruffle some feathers. We started tossing around the idea of a giant Soviet flag mysteriously appearing somewhere around town.

The first canvas to consider is always the city water tower: Large, imposing, 360-degree visibility, the center of town, and illuminated at night. But that meant scaling a fence and climbing a considerable distance carrying supplies, all under spotlights. Not good. The next backdrop was equally appealing: the Dairy Queen with its large red roof. We would only need to supply the yellow hammer, sickle and star to complete the flag.

So we set about hatching a plan early that summer. Joe and I rummaged around and found some cardboard refrigerator boxes and took them to his garage. Joe was more artistic than me, so he drew out a clean, sweeping arc for the sickle and crisp outlines for the hammer and star. Then we set about cutting the cardboard for our giant template.

After further consideration, the Dairy Queen seemed a little risky. Even at 3:00 a.m., there is occasional traffic, and the police station is just down the street.

We eventually landed on a location that was secluded at night but very visible in the daylight: the large retaining wall on the north end of Lake Maloney. It was July, so the east-beach camping area immediately adjacent to the wall would provide a good audience for our artwork, and there would be plenty of boat traffic in that area.

Late on a sultry Saturday night on July 12, 1980, my brother and I loaded up the cardboard templates, a gallon of red paint, a brush, roller and pan, a couple of cans of yellow spray paint and some beer. If memory serves me, Joe was at some social event that night and we couldn’t reach him.

Jim drove us out to the lake in our brown 1977 Grand Torino to a spot close enough to the campground for maximum visibility, yet far enough away to avoid nighttime detection. We hiked up the earthen backside of the dam, scaled the low lip on top of the concrete wall and descended the sloping concrete face to survey our canvas.

The concrete slab was laid out perfectly for a flag: the vertical concrete relief cuts are spaced about every 15 feet, and each rectangular section is about 10 feet high. We set about rolling the red paint to completely cover one 10x15 foot section. With the roller, the job went very fast. Then we stopped for a half hour or so to have a beer, admire the rich western Nebraska star field and give that paint a little time to dry.

Next, we set the cardboard templates in place and started covering the cutout areas with bright yellow paint. From start to finish it probably took us about 45 minutes. We packed the templates, paint and tools back in the Torino and drove home with smirks on our faces and red paint on our legs. At home we smuggled the cardboard and leftover supplies downstairs to the basement and went to bed.

Sunday was an unremarkable day. I think we probably called Joe to tell him the deed was done, and he was pissed that he missed out.

Monday was different.

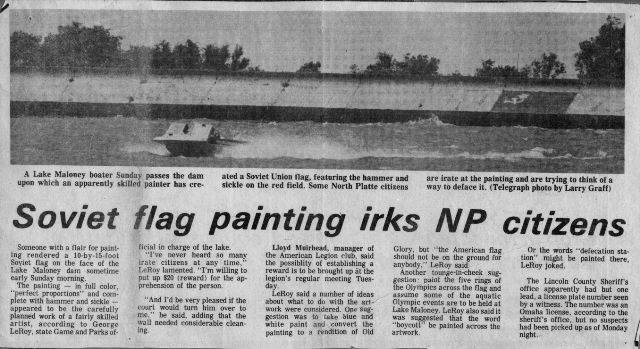

Monday morning, my parents brought the North Platte Telegraph newspaper into the house and the proverbial feces hit the fan. Taking up approximately ¼ of the front page was a large black & white photo of our artwork with the caption, Soviet flag painting irks NP citizens. A motorboat in the foreground showed the huge scale of the flag, clearly visible from probably a mile away.

I felt like the kid at the circus who pokes the caged lion with the stick to get a reaction—but the reaction is much scarier than anticipated.

I don’t remember at what point my father descended the basement steps that day, but he quickly found the paint-splattered cardboard templates, hastily concealed behind his workbench.

I took the dog for a walk.

I shirked from every house knowing that practically every residence was just then spreading the morning paper on the table, jaws dropping in unison.

I read the article with a lump in my throat. A state Game & Parks official was offering a $20 reward for my capture; the local American Legion was devoting a meeting to discuss my eventual punishment. My God! I was a fugitive with a price on my head!

On the other hand, the article was very complementary: They surmised that it was the work of a “fairly skilled artist” with “perfect proportions” (the reporter and the commenting authorities, like us, failed to realize that the star should have been a hollow outline). My father fully expected to wake up to a cross burning in our front yard.

As the initial shock of massive publicity wore off, and the whole city began buzzing with the news, my ego slowly began to inflate. I was at the center of everything; it was mine and Jim’s and Joe’s huge prank, and we had successfully pulled it off! To possess this magnitude of secret news was simply too much for a 15 year old. I started to tell a few friends, who naturally dismissed such a ridiculous claim. So I rolled up my pant legs to show the scarlet proof. I was suddenly a Tom Sawyer-esque hero/celebrity.

As soon as the first story ran, a mob of citizens flocked to the scene of the crime to deface the offensive, politically-charged image. Several gallons of paint were dumped across the flag; messages, both patriotic and threatening, were added on top of the newly dumped paint: “America: Love it or Leave It.” “Commies must die” and “We love America,” all hastily scrawled and many grammatically flawed.

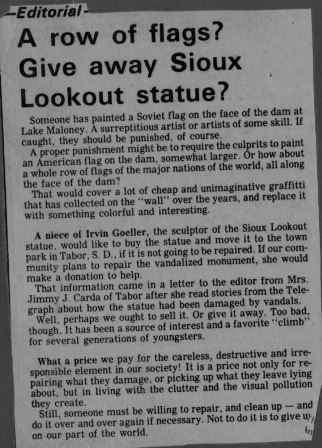

To my surprise, the publicity was only beginning. The Omaha World Herald and the Denver Post picked up the story a day later, followed by a Telegraph editorial about vandalism.

On Thursday morning, a new picture adorned the Telegraph front page: a local steam cleaning company brought out their industrial equipment to clean the flag and the resulting emblazoned threats.

My favorite publicity nugget was in the form of a letter to the editor. The author suggested that communists were infiltrating North Platte, Nebraska, and urged citizens to become educated through such groups as the John Birch Society!

At some point during the week, word among my friends in this small city spread. I was upstairs, getting ready to go to the restaurant where I worked as a dishwasher. Mom came upstairs to inform me that the Sherriff wanted to have a word with me. I reluctantly came downstairs to face the consequences. He said he had heard a rumor that I had something to do with the flag painting. Was it true?

Being an easily intimidated 15-year old, I confessed on the spot. He thanked me for my honesty, issued a citation and left. By that point, my parents had grounded me, except for work. Somehow, my brother and I were savvy enough to realize that the newspaper is not allowed to print the names of juvenile offenders under the age of 16. Since I was 15, and my brother was 17, I accepted the blame. Defacing public property is a third-degree misdemeanor. Never mind that there were a hundred other graffiti examples already on the wall. After procuring several character reference letters from the community (my scout leader, coaches, teachers, etc.), I received six months of probation and a $100 fine to pay for the steam cleaning company (which my brother paid).

Now fast forward a couple of years. I was sitting in 20th century history class, studying the period following World War II and the beginning of the Joe McCarthy era. The teacher had introduced us to the HUAC—the House Un-American Activities Committee and asked if anyone could think of an example of an activity that the HUAC might disapprove of.

Kraig Baade’s arm shot up, and he stated in a voice mixed with patriotism and defiance, “I’ll tell you something un-American: That communist flag someone painted on the wall.” I immediately felt the effects of an adrenaline rush. My heart leapt into my throat and I fought to keep my bowels from emptying on the spot. Time stood still for me and I waited for the entire room of classmates to spin around in unison with riveting eyes focused on me.

“Good example, Kraig.” And he moved on with his lecture.